Tags

20th century history, BGSU Historu, Braxton Howard, Donna M. Neiman Award, Easter Rising, Ireland

By: Braxton Howard, 2023 Award Winner of the Donna M. Neiman Award, Senior History Major

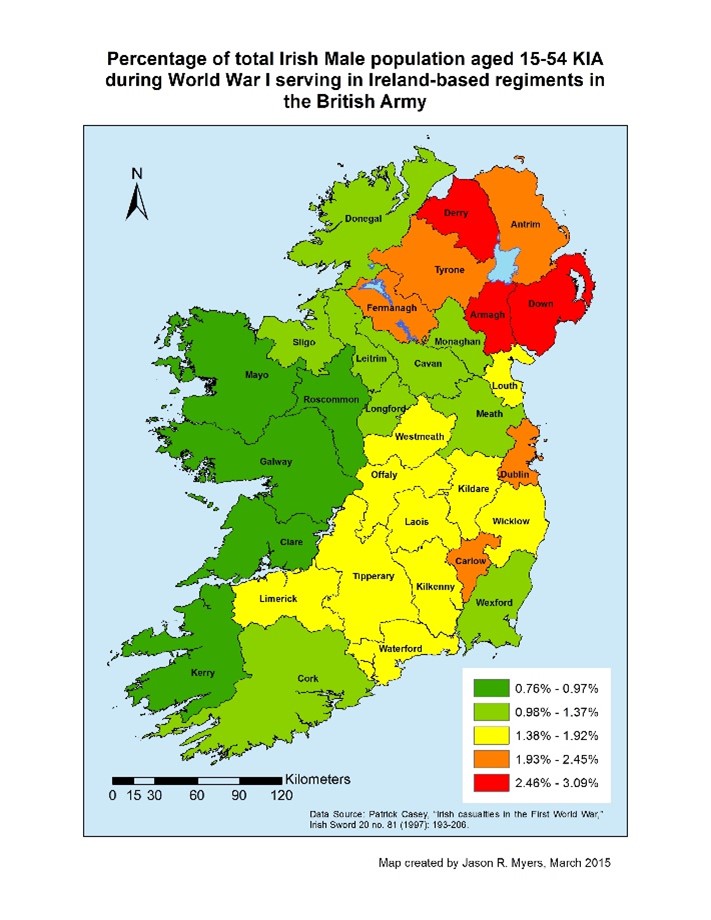

This is a public presentation of a paper originally written for HIST 4805: Revolutions in World History, taught by Dr. Michael Brooks. Although shortened to the essentials, this post aims to outline the ways that the relatively short Easter Rising of 1916 could bring to light divides that had grown among the Irish people, which would bring over a century of contention exhibited not only through a war for independence and the Troubles, but also equally contentious works of history. These divisions – an intertwined mixture of views on British rule and religious belief – would come to a boiling point as frustrations with the British grew in reaction to representation issues, the Irish Famine in the 1840s, and, at the time of the Rising, World War I drafts. Religion had long been a point of conflict among the Irish, with British attempts to convert them to Protestantism, often by force, occurring regularly and finding the most success in Northern Ireland.

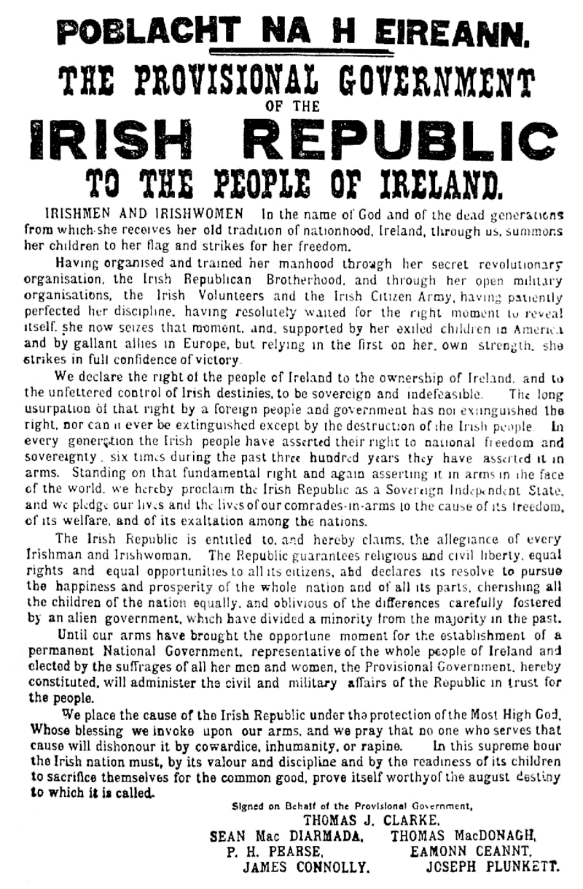

This point would become more strained as each side marginalized each other, and began to associate with political movements: the Catholics being sympathetic to Irish nationalists and the Protestants to the Unionists, on the side of the British. Those seeking independence from England would soon become known as “Fenians,” while those seeking union were called “Oranges,” with religious beliefs and location (southern or northern Ireland, respectively) being key to their politics (Lee, 49-59).[1] On top of these tensions, the economic crises and belated enactments in response to the famine and property ownership contributed to a push for Irish Home Rule in the 1860s. While it failed, a seed was planted in the minds of the Irish which would blossom into the party Sinn Fein, meaning “we ourselves” in the Irish language (Rumpf, 6-10). It was this party of nationalists, as well as the socialist and feminist movements, who would see themselves joined together in solidarity under the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) as they stood together against the British during the Rising (McKenna, 1). These tensions would only increase during the Easter Rising, eventually culminating in the Irish Civil War of 1923, the later Troubles, and still show themselves today in the presentation of this period among historical authorship.

Despite its influence, the Easter Rising itself was a rather short affair, only lasting 6 days. While the Northern (protestant) Irish supported involvement in the World War, the South was openly hostile to it, with James Connolly being a notable leader in this movement. Connolly argued for sympathy toward the Germans in his speech “The War upon the German Nation,” while painting the British as both hostile and oppressors. He discouraged any Irish from joining the British side likening such an act to dying for the enemy (Connolly, 243-249). The Germans took note of this and attempted to send the IRB weapons (which would never arrive), encouraging the Southern Irish to act and setting in motion the ill-fated Rising. The IRB planned to have their volunteer armies parade through various cities, but then when organized in this manner, they would instead move to capture key British positions. However, internal disagreements arose, which resulted in the message not being spread well, and the Rising only occurring properly in Dublin on Easter Monday (McGarry, 240-247).

Regardless of this setback, those in Dublin moved forward with the plan on Monday, April 23, 1916, even as they anticipated its failure. The British were able to quickly ship in military men and arms to crush the rebellion, resulting in the IRB ordering surrender by April 29 after little progress. The British Army, however, had been reckless in Dublin and caused a significant number of civilian casualties and damages, which had begun to change the direction of public opinion from ambivalence toward independence. Further, the British showed no mercy to the revolutionaries, executing the leaders and arresting numerous others. These executions resulted in these leaders becoming martyred by the Irish republican movement, which combined with the civilian casualties, proved to cause an overnight change in public opinion in favor of the IRB (McGarry, 249-255).

While this is a glimpse into the Rising itself, equally important is the lasting effect on the Irish it has had, both in the form of the aforementioned historical events it helped inspire, and in interpretations of it proposed by historians. From nationalist and unionist views to attempts at historical revisionism and increased tension during the Troubles to new and old approaches in the centenary era today, the historiography of the Rising and Irish independence is as troubled by contention as the period it studies. As one author, Charles Townshend puts it, even the terms used to define just what had occurred were themselves a point of contention depending upon the leanings of the writer. Throughout the century since the Rising, it and the later War for Independence have been referred to as everything from a takeover to terrorism or a revolution. And scholarship on the subject ranges just as widely: from a war of independence, to a social revolution, a religious revolution, and yet more (Townsend, 2-9). However, certain narrative approaches would come to dominate historical interpretations of the Rising, falling into two categories in the era contemporary to the Rising and Irish Independence: these being the Irish Free State’s narrative and the Northern Irish/English narrative.

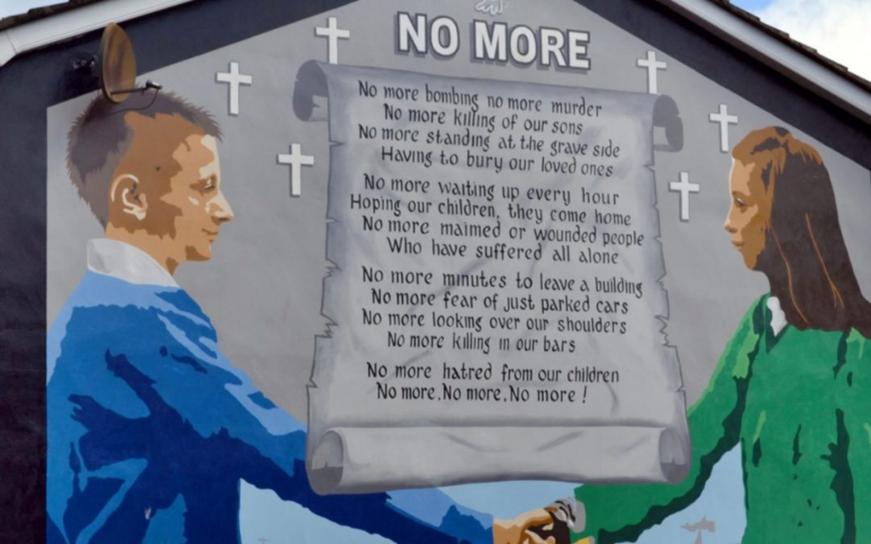

Beyond just historical writings, the popular imagination was also influenced through literature, such as the poems of W.B. Yeats, and even through Northern and Southern museums and education. Not long after gaining their independence, the new Irish Free State sought to represent the events of their newfound freedom in their National Museum of Ireland. They planned to use it as a national symbol of unity and patriotism, especially through the “Easter Week Collection” (Joye, 180-184). Meanwhile, Northern Ireland created a different presentation of the events, where they showcased the period as a republican insurrection. Central to this depiction, historian Elizabeth Crooke argues, is a “story of absence,” where a great portion of the events and their unfolding nature were neglected by the Northern Irish museums, or even mocked, as shown in the case of an “unsightly umbrella” they stated to have been used by Pearse. Crooke states in no unclear terms that many historians attribute these commemorations for the public by museums as a primary factor in the beginning of the Troubles (Crooke, 194-196).

Over the proceeding decades, new approaches would be developed by historians. The narratives that took shape in these later years developed again into two primary schools: revisionist and anti-revisionist, themselves representing Unionist and Nationalist biases, respectively. This era (roughly the 1960s to the 1990s) saw both the Troubles and access to newfound sources, which resulted in authors such as F.X. Martin and Francis Shaw taking a revisionist approach as they questioned how valorous the Citizen’s Army was, or if the near messianic remembrance of Patrick Pearce was appropriate, among other such topics (O’Tuathaigh, 876). While these scholars among others attempted to separate the truth from the patriotic myth that had begun to take root in Ireland, anti-revisionists quickly sprouted up throughout the Troubles, such as Brendan Bradshaw, who labeled them as neo-unionists who were “anti-Ireland,” due to the revisionists placing blame on nationalists for twisting history for their own narrative (Perry, 163-166).

The approach of present-day historiography would see yet further reevaluations of these conflicts in opinion and approach, as the Troubles’ deep wounds soon took their toll on the Irish. The use of such heavy violence during this era would lead historians to question their hardline approaches from the previous era. This would result in a move away from glorifying the use of force to gain a unified Ireland as historians from both sides sought new ideological considerations in order to create a framework for a peaceful “shared Ireland” (O’Tuathaigh, 868-869). Presently, some historians argue that these previous writers impressed their own ideologies on the Rising, turning the era into a battleground of interpretations. Meanwhile, while debate continues in this field, new discussions have also been opened, from the important – and often neglected – role of women in the Rising, to explorations in the part played by factors such as class and religion. Though it was a revolution of less than a week in length, the Easter Rising of 1916 continues to spark debate among both historians and the Irish themselves. Now, with the recent centenary of both the Rising and the Irish War of Independence, interest, debate, and scholarship is unlikely to dissipate any time soon.

Sources Cited:

Connolly, James. James Connolly: Selected Writings. Edited by P. Berresford Ellis. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1973.

Crooke, Elizabeth. “A Story of Absence and Recovery; the Easter Rising in Museums in Northern Ireland.” In Making 1916: Material and Visual Culture of the Easter Rising, edited by Lisa Godson and Joanna Bruck, 194-202. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 2015.

Joye, Lar and Brenda Malone. “Displaying the Nation: the 1916 Exhibition at the National Museum of Ireland.” In Making 1916: Material and Visual Culture of the Easter Rising, edited by Lisa Godson and Joanna Bruck, 180-193. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 2015.

Lee, Joseph. The Modernization of Irish Society: 1848-1918. Dublin, Ireland: Gill and Macmillian, Ltd., 1973.

McGarry, Fearghal. “The Easter Ring.” In Atlas of the Irish Revolution, edited by John Crowley, Donal O’Drisceoil, and Mike Murphy, Cork, 240-257. Ireland: Cork University Press, 2017.

McKenna, Joseph. Women in the Struggle for Irish Independence. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2019.

O’Tuathaigh, Gearoid. “The Historiography of the Irish Revolution.” In Atlas of the Irish Revolution, edited by John Crowley, Donal O’Drisceoil, and Mike Murphy, 864-873. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2017.

Perry, Robert. “Revising Irish history: The Northern Ireland Conflict and the War of Ideas.” Journal of European Studies 40, no. 4 (2010): 329-354. doi:10.1177/0047244110382170.

Rumpf, E. and A. C. Hepburn. Nationalism and Socialism in Twentieth-Century Ireland. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1977.

Townsend, Charles. “Historiography: Telling the Irish Revolution.” In The Irish Revolution 1913-1923, edited Joost Augusteijn, 1-16. New York: PALGRAVE, 2002.

Further Reading:

Crowley, John, Donal O’Drisceoil, and Mike Murphey. Atlas of the Irish Revolution. Cork, Ireland: Cork University Press, 2017.

Godson, Lisa, and Joanna Bruck. Making 1916: Material and Visual Culture of the Easter Rising. Liverpool, UK: Liverpool University Press, 2015.

Grayson, Richard S., and Fearghal McGarry. Remembering 1916: The Easter Rising, the Somme and the Politics of Memory in Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.