Tags

Ancient History, BGSU History, BGSU Study Abroad, Casey Stark, Jo Enger Arthur Scholarship for Study Abroad, Roma Aeterna, Rome, Undergraduate

By: Dr. Casey Stark, BGSU Associate Teaching Professor, Roma Aeterna Summer 2023 Instructor

This experience began several years ago with BGSU’s encouragement of faculty to lead short education abroad programs, and the idea, “Why not study Roman history in Rome?”.

As a historian of Ancient Rome, I’m fully cognizant of how difficult it is to wrap our heads around the history and geography of a city that was founded – at least according to the Romans – in 753 BCE and over the centuries grew to a capital of approximately one million people and the center of an empire. With the increase in digital technologies, it has become easier to provide students with a more comprehensive idea of the evolution of the city’s development, expansion and building projects, and what living in ancient Rome would have been like, but this education abroad experience took things up a level (or two or three).

On May 17, twelve students, one Director/ancient history professor (me), and one Co-Director (my “Communications Director”, Julian Gillilan, Education Abroad Student Advisor and alum of the History M.A. program) left for our Roman adventure. The program itself was called Roma Aeterna (“Eternal Rome”) and it was designed to give students an immersive experiential learning opportunity to study ancient Roman history and to live in a foreign city for long enough that they felt like more than just tourists. With the assistance of BGSU’s partner language school for Italian, the Centro Linguistico Italiano Dante Alighieri (CLIDA), we were housed in Roman apartments, provided classroom space at the school, and generally made welcome through our departure on June 6.

So, what could go wrong in Rome? Thankfully, nothing too serious, but we had our share of adversities. Although most Romans understand and speak some English, there was still at times a language barrier. Italian apartments are quirky by American standards and learning how to manage these spaces and their appliances were their own learning experiences (I faced possible electrocution each time I used my washing machine). Pickpocketing is probably the number one concern in Rome, especially at major tourist sites and on the Metro, and we unfortunately did not leave Rome unscathed.

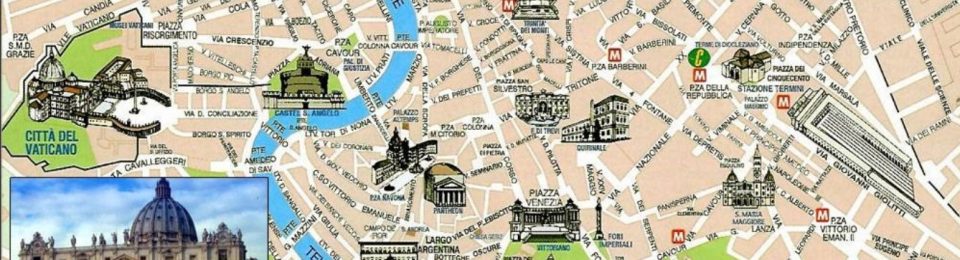

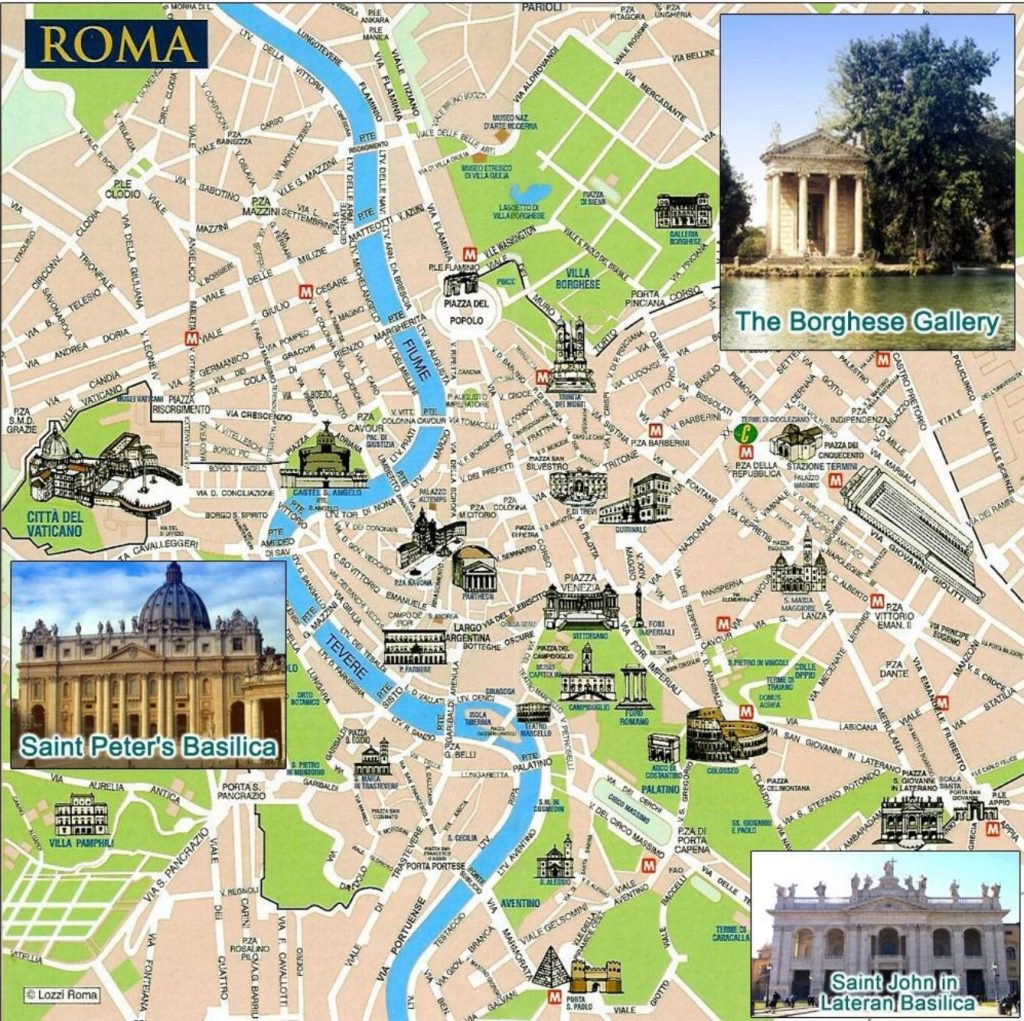

Moving around any major city can be a challenge. The Metro lines are easy to use and run regularly, but do not cover the entire city and you can be squashed in like sardines at rush hour. You need to use buses to get to the rest of the city, and bus “schedules” are more like suggestions. It’s often most efficient to go on foot, and since the ancient city was more compressed than the modern, these locations are within walking distance of one another. However, this also meant that there were several days on the trip when we walked around ten miles including lots of stairs and uneven streets. Blisters and turned ankles happened. Then there was the threat of moving vehicles; several of us had multiple close encounters with scooters, cars, and buses (not all were our fault).

Unavailable sites were also an issue and a few locations on our agenda were unfortunately closed. For the record, I’m now zero for two trying to get inside the Mausoleum of Augustus. Also “The Boss” (Bruce Springsteen) came to town and gave a concert at the Circus Maximus, so our first attempt to walk on Rome’s most famous racetrack was thwarted. However, this brought up from the beginning of our trip how people today live in, among, and with more than 2500 years of archaeological remains literally on their doorsteps – not to mention under them. It still amazes me how Romans have these ancient historical monuments embedded into their landscape and may or may not realize what they are. Or care.

It’s also a different way of thinking about historical preservation and the use of ancient spaces in modern contexts. Is preserving the past more important than the quality of life of people living in Rome today? Should “modern” (I use the term loosely) structures be removed to uncover more of the ancient city? Is it best for ancient monuments like the Baths of Caracalla which are now used for outdoor concerts or the Baths of Diocletian which house part of the National Museum to be structurally altered, repurposed, and even damaged if it ensures their survival?

This post also serves as an introduction to a series of blogs that will be published over the next few weeks on specific sites we visited. The course covered ancient Roman history in its approximate chronological order, and a typical day included class in the morning followed by site visits in the afternoon to see what we had just discussed. Several students chose to write blog posts in partial complement of their course requirements, and in similar fashion, these will be presented in the order we visited that site. Those located in the city of Rome can be found in Figure 1.

Hope London writes about Tibur Island, located on the river of the same name that flows through the city, and she discusses how the island’s main purposes have remained the same for over 2000 years. [May 20]

Nathaniel Brooks takes us to Ostia Antica outside the city. It was Rome’s first port and the two were connected by the Tiber River. In antiquity it was on the coastline of the Tyrrhenian Sea but is now two miles inland. [May 21]

Abbey Staats covers more than 2000 years of history in her discussion of the Largo Argentina, from its construction and the assassination of Julius Caesar to newly reopened archeological site and cat sanctuary. [May 23]

Alex Eckhart presents the history of the area around the Theater of Marcellus. Although the latter is the most extant structure, the area once included a Temple of Apollo “Sosianus” and the Circus Flamininus. [May 23]

Joseph DeSario discusses the history of the Pantheon, a Roman temple dedicated to all the gods, and its evolution to a Christian church and final resting place of artists and kings. [May 24] *Update: starting July 3, there is now a 5 euro entrance fee to this formerly free site. *

Next is a double feature from our (long) day trip to Pompeii, one of the cities along the Bay of Naples that was destroyed in the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE. [May 28]

Sabrina Sprague provides an overview of the history and geology of the area, historical context for the eruption, and preservation efforts and their challenges.

Maggie Fuller approaches the history of the city from the perspective of social cohesion, arguing that Pompeii’s archeological remains show distinct differences in class and citizenship.

Peter Strzempka takes us to Vatican City – technically a state within the city of Rome and the only place where Latin is still an official language – and covers how this site, originally a Roman Circus, became a Christian center and the location of St. Peter’s Basilica. [May 31]

Dylan Smith keeps us on the west bank of the Tibur River with his discussion of Castel Sant’Angelo. Originally constructed as a funerary monument for the emperor Hadrian and his family, the structure has been pillaged, altered, and repurposed several times. [June 2]

These blogs are by no means an exhaustive list of what we did during our time in Rome; rather they provide a small sample of the ancient sites that can still be seen in the city and their complex histories.

In all, the trip was a success. From an instructional standpoint, students met their learning objectives and covered the necessary historical content. However, it’s the experiential learning opportunities that give programs like this one the most value. Nothing compares to visiting, for example, the Roman Forum in person; walking among centuries of history in one location, standing by (if not directly under) a triumphal arch, assessing that the Temple of Vesta is smaller than expected, seeing the Colosseum in one direction and in another the Palatine Hill where Rome’s Emperors lived and literally looked down on the city’s political and religious center. Of different but arguably equal importance are the experiences that are the natural byproducts of education abroad. For some students this trip was their first time on an airplane. For many it was their first time out of the country or the longest they had been away from home. Most had never lived in a large city, and they did so like modern Romans. They relied on public transportation. They ate all the gelato, pizza, and Rome’s four pastas. They photographed and logged their experiences. They made memories and brought back souvenirs. They left more independent than when they arrived. And everyone made it home safely.

References

Gates, Guilbert. In “The Fall and Rise and Fall of Pompeii,” by Joshua Hammer. Smithsonian Magazine. July 2015. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fall-rise-fall-pompeii-180955732/

Ostia Antica map. In “The Quiet Port: Ostia Antica, Italy,” by Ian Fisher. The New York Times. Sept. 17, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/17/travel/10dayout.html

Rome map 3. 1004×998 pixels. “Orange Smile”. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://www.orangesmile.com/common/img_city_maps/rome-map-3.jpg