Tags

BGSU alum Joe Faykosh was recently quoted in the New York Times article: Even Without Its Most Famous Son, Carter’s Hometown Remains a Destination.

Continue reading17 Friday Jan 2025

Posted in Alumni News

≈ Comments Off on BGSU Alum Quoted in the NY Times on President Carter’s Legacy

Tags

BGSU alum Joe Faykosh was recently quoted in the New York Times article: Even Without Its Most Famous Son, Carter’s Hometown Remains a Destination.

Continue reading03 Friday Jan 2025

Posted in Faculty News

≈ Comments Off on BGSU History Professor Appears in WWII Documentaries

Dr. Walter Grunden is a Professor of History at BGSU, where he specializes in Policy History, Modern China and Japan.

He recently lent his expertise to several documentaries covering scientific knowledge, international subterfuge, and WWII. He shares with us some of the projects he’s worked on recently, how Williams 141 was transformed into a recording studio, and where you can watch the documentaries.

Continue reading21 Thursday Nov 2024

Posted in Alumni News, Faculty News

≈ Comments Off on Dr. Green Delivers Talk on the Life and Legacy of Ella P. Stewart

Dr. Shirley Green, Adjunct History Instructor at BGSU and the University of Toledo, delivered a talk on the Life and Legacy of Ella P. Stewart, one of the nation’s first Black female pharmacists.

Continue reading14 Thursday Nov 2024

Posted in Events

≈ Comments Off on Dr. Francis Gavin encourages students to look to the future with his “Reflections on Nuclear History”

Inheriting a world with nuclear weapons is like “buying a house with a ghost in it – you never really get a good night’s sleep, because you always know the ghost is there.”

Continue reading14 Saturday Sep 2024

Posted in Department News

≈ Comments Off on Meet Our New Senior Secretary!

Tags

Get to know our new senior secretary, Angie Legg!

She has not worked with BGSU before, but has had experience in various city and county offices. She especially enjoys working with people and the public, its challenges and rewards. She appreciates history and its study of it as, as she tells it, an important link between the understanding of where we came from and where we are headed, as well as it gives us an understanding of how past events have shaped the world we live in today.

She is looking forward to being part of our staff and helping students prepare for the future in that history! Her office hours are Monday through Friday 8pm to 5pm!

09 Thursday May 2024

Posted in Events

≈ Comments Off on Northwest Ohio Students Qualify for National History Day Contest

Tags

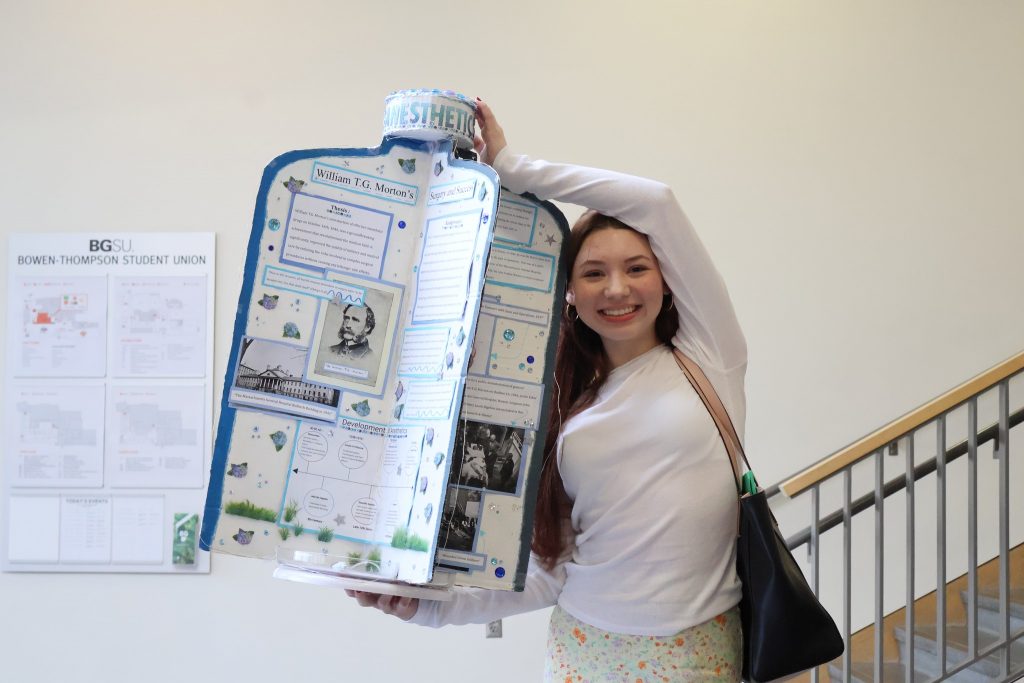

Each spring, the Student Union at BGSU welcomes middle and high school students from Northwest Ohio to compete in the Region 1 Contest of Ohio History Day. Students create tabletop displays, documentaries, websites, performances, and papers, then bring them to the Regional Contest for judging and feedback.

01 Wednesday May 2024

Posted in Department News

≈ Comments Off on BGSU History Grad Conducts Research for the South Carolina Oyotunji African Village

BGSU Department of History master’s student, Oluwatimilehin Fatoki, had interned and researched in the South Carolina’s Oyotunji African Village, writing on the significance of the “spirital ecosystem” and the significance of cultural resilience and preservation of African culture in the United States. Below is his thesis, titled “The Yoruba Gods in Oyotunji, South Carolina: a Case Study of Religio-Cultural Africanisms in the Americas”.

Continue reading18 Thursday Apr 2024

Posted in Department News, Events, Graduate Student News, Public History, Public history project

≈ Comments Off on “Eclipsing History” Podcast at National Council on Public History Conference

Emily Shaver Kay and Peter Limbert, students in the History M.A. program, presented a poster about the Eclipsing History podcast in the National Council for Public History annual conference in Salt Lake City.

The poster gathered good attention and multiple attendees scanned the QR code to open up the season! Those who engaged with the presenters and the poster commented on how innovative the class which constructed the podcast sounded and that it covers perspectives and topics usually left behind in the history field, like Indigenous knowledge and contribution to American history and Western scientific thought. There was also great interest in the digital history skills that students learned. Congratulations on the presenters and everyone in the class for this success!

29 Friday Mar 2024

Posted in Alumni News, Department News

≈ Comments Off on BGSU History Alum Shares Memory, Career, and Crossword Puzzles!

Tags

A few weeks ago we featured a crossword by Tim Beatty, a retired teacher and alum. Tim Beatty grew up in Swanton, Ohio, forty minutes northwest of Bowling Green. He attended Bowling Green State University (BGSU) between 1969 and 1976, earning both his Bachelor’s and his Master’s in history and American Culture Studies. He remembers fondly Robert Twyman as one of his history professors, enjoying the courses he taught.

Continue reading05 Tuesday Dec 2023

Posted in Events, Faculty News, Featured, Public History

≈ Comments Off on Dr. Doug Forsyth Delivers Talk about Researching Family History

Click here to listen to Doug Forsyth’s interview about the project with London Mitchell of “Staying in Contact” podcast

When you receive an envelope containing a Confederate bullet in a box of family documents, you’re going to be inspired to do a little digging.

Continue reading