By Chase Fleece, Graduate Student in the Department of History at BGSU

In the small hours of August 25, 1934, the residents of McGuffey, Ohio–a small rural community fifty-five miles southwest of Bowling Green–slept peacefully following a rather uneventful afternoon. Since mid-June, the monotony most McGuffians enjoyed had been disrupted by sporadic squabbles between union organizers and anti-union deputies. Organized with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), AWFLU 19724 comprised nearly 800 local farmworkers and sharecroppers who weeded, topped, and harvested the Scioto Marsh’s many onions. To many their demands were simple: increased wages and an eight-hour workday. Yet growers had refused to negotiate and confrontations continued. Then, at three o’clock in the morning, a charge of nitroglycerin ripped through McGuffey Mayor Godfrey Ott’s home breaking windows and caving in the southside walls. Luckily, no one was injured in the blast – but more violence was yet to come.

Above: These “riot squads” consisted of locally deputized veterans of the First World War who, as the original caption suggests, “took care of trouble as it came up.” Photograph courtesy of the Hardin County Historical Museum.

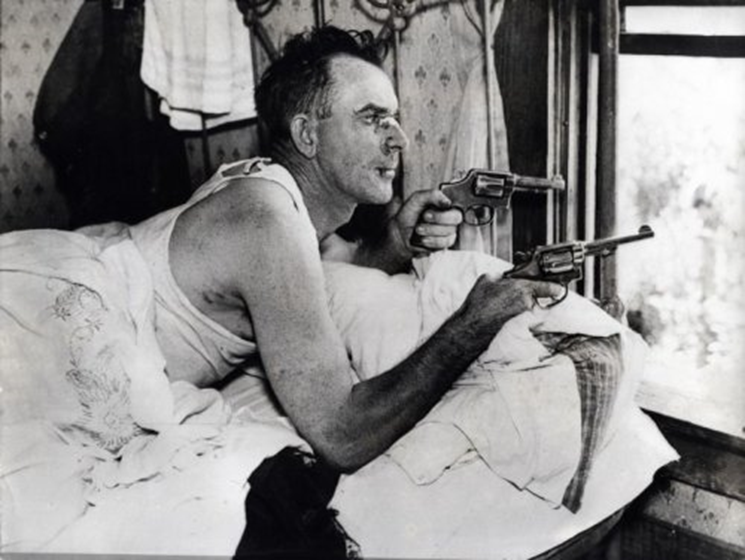

The next morning anti-unionist vigilantes poured into the village 300 to 500 strong. Scores of men and women brandishing firearms patrolled the streets. No one was safe; especially not Okey Odell, AWFLU’s President. Odell, a thirty-nine-year-old from West Virginia, was able to avoid capture for only so long before he fell under the mob’s control (though how remains contested). He was beaten, thrown into the bed of a pickup truck, and driven to the Allen County line. Though warned not to return, a battered Odell, suffering from broken ribs and countless scrapes and bruises, stumbled back into town just a few hours later. Standing defiantly on his porch Odell antagonized his captors, revolver in hand, challenging anyone brave enough to “come and get me.”[1] The challenge went uncontested. In the following days, however, the crowds dispersed and tensions settled. Unfortunately, the bombing ended the union’s chances of achieving any meaningful concessions. Speaking to reporters on August 29, 1934, Mayor Ott declared “There is no strike here anymore.”[2]

[1] “Anti-Unionists Seize Ohio Town After Mayor’s Home is Bombed,” New York Times, August 26, 1934.

[2] Kenton News Republican, August 29, 1934.

Above: A battered Okey Odell brandishes two revolvers as he keeps a watchful eye on the vigilantes patrolling McGuffey’s streets. “Strike Leader,” Bureau County Tribune, September 14, 1934.

These were just some of the events I highlighted as I stood before nearly sixty community members gathered in McGuffey, Ohio, on August 25, 2024, to reflect on the ninetieth anniversary of the Hardin County Onion Pickers Strike. The strike, which has been largely understudied (outside Dr. Brooks’ “Ohio History” class, that is!) by scholars, will be explored further in my forthcoming master’s thesis “Mayhem in the Muck: An Environmental and Labor History of Ohio’s Scioto Marsh.” It was based on this research that I was so honored to have been asked by the McGuffey Memories Historical Society to share my findings with the broader community on such a milestone. It also got me thinking about the importance of publicly facing scholarship. To illustrate this point, I will share a quick anecdote. Before I began my remarks, I surveyed the room by asking attendees to raise their hands if they knew someone who had worked on the marsh; nearly every hand rose. Afterward, as I collected my notes, an elderly gentleman approached me to share his own experiences in the fields. As he spoke, I listened attentively to him describe the arduous task of weeding onions in the oppressive heat for mere cents on the dollar; a job he held while just a kid. He thanked me and walked off. It is those memories and experiences that exemplify the importance of local history. As scholars have demonstrated time and time again, local historical knowledge, which originates from the communities themselves, is a powerful force. It complements and informs the work we, as academic historians, do every day. As W.G. Hoskins famously quipped “The historian should not be afraid to get his feet wet.” I am glad I followed that advice.

Above: The crowd who attended Chase Fleece’s community presentation “Boom! Goes the Marsh: The 90th Anniversary of the Onion Pickers Strike, 1934-2024.”

If you would like to learn more about my project, you can listen to my interview with Dennis Beverly on 95.3 WKTN’s “Public Eye” program. Dennis and I chatted for about thirty minutes on a variety of topics but mostly I gave a brief overview of the Scioto Marsh’s rich history!