Tags

BGSU History, BGSU Study Abroad, Casey Stark, Jo Enger Arthur Scholarship for Study Abroad, Peter Strzempka, Roma Aeterna, Rome, St. Peter's Basilica, Undergraduate

By: Peter Strzempka, BGSU Roma Aeterna 2023 Student

When one first enters Vatican City, St. Peter’s Basilica is undoubtedly the first thing everyone notices. However, one does not get a great view of the Basilica until they enter through the entrance on the north side of the oval Piazza San Pietro, where the massive structure is finally visible up close and personal. The façade, decorated beautifully with marble columns and statues of the most important Church fathers, overwhelms the viewer with seemingly endless detail. What most people do not realize about St. Peter’s is its long and illustrious history, both the Old and modern St. Peter’s. Much of the old structure and pre-Christian sites underneath have been overshadowed by perhaps the most important church in Roman Catholicism, but their stories are crucial to the foundation of the basilica we see today. This blog will start from the beginning, with St. Peter’s execution and the construction of Old St. Peter’s, and proceed through the Counter-Reformation, the period in which the St. Peter’s we know today was finished. Through this brief overview, the goal is to gain a greater understanding and appreciation for all who visit the basilica, whether for pilgrimage or tourism.

St. Peter, chief of the Apostles, after years of preaching in Galilee, had decided to move on to Rome, where he supposedly sat as the first Bishop of Rome for twenty-five years before being executed by Nero as a response to the Great Fire of Rome1. He was said to have been crucified, the typical method for non-Romans, but Peter refused to be killed the same way as Christ, so he was crucified upside down. Afterwards, his body was buried not far away, where a shrine was erected and pilgrimages to the shrine would slowly start to increase over the first few decades after his death, but due to his burial in a public cemetery, the exact location was never fully known.

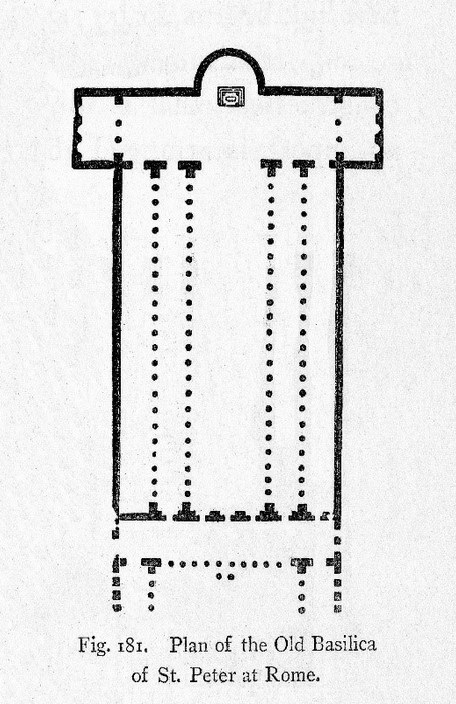

It was not until Constantine the Great, in the year 320 C.E., that the tomb was fully enclosed under a building, known today as Old St. Peter’s Basilica2. Old St. Peter’s would have been a massive structure for the time. The nave, or the main portion of the church where the congregation would sit, was over 300 feet long and the ceilings around 105 feet tall. The Basilica was constructed in the shape of a Tau cross, the symbol of Christianity at the time, instead of the cruciform cross that gained popularity in the late Renaissance. At the time, the only other major church was St. John Lateran, built by Constantine as the seat of Christianity before construction of St. Peter’s. St. John Lateran would actually remain the seat of the Pope until the 15th century, making the original intention of St. Peter’s to “glorify the burial place of Rome’s first bishop and Prince of the Apostles”3. The basilica was naturally centered on the tomb of St. Peter, with the apse holding the tomb. However, his supposed tomb was only one of many Christian burials on the side of the Vatican Hill, which made construction difficult. Constantine had to fill in the graves, something that was illegal even for an Emperor, but Constantine insisted due to the importance of the site4. The back of the basilica had to be embedded in the hill, while the front was 25 feet above original ground level, making this an extremely difficult construction. Before it was a cemetery, the southern end of the hill was a Roman Circus, supposedly where Peter himself was martyred, with the largest Egyptian obelisk in Rome decorating the spina of the track. This track would also be filled in partially and built over top, but the obelisk would remain for over another thousand years. Sadly, not much is known about the interior design of Old St. Peter’s, but we know it was decorated with hundreds of Greek marble pillars and had a large open space to awe the congregations.

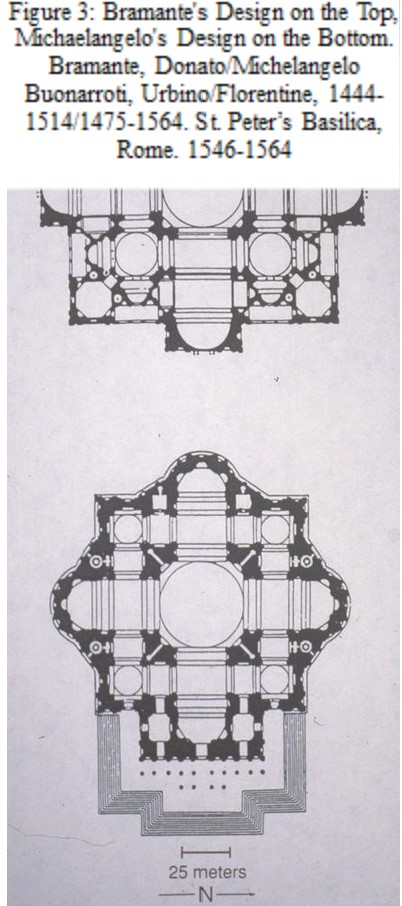

Old St. Peter’s would remain unchanged for over 1200 years, even falling into disrepair in certain sections. The southern wall was falling apart, and Pope Julius II claimed it was dilapidated5. It was under Pope Nicholas V that some remodeling began, but it was Julius II who is credited with starting the complete reconstruction of a new basilica on the site of Old St. Peter’s, starting in 1506. Where Nicholas V intended to restore and add to Old St. Peter’s, Julius II, with his chosen architect Donato Bramante, wanted to demolish the Old St. Peter’s. This was a hotly debated issue of the day, as it would require demolishing dozens of tombs of early Popes buried there6. Bramante’s original plans are still debated today, but it is agreed upon that it would be centered around a large dome and built around the Old St. Peter’s to allow services to continue. It would be shaped as a square with an equilateral cross in the center, decorated in typical baroque features. Bramante designed his version of the dome after the Pantheon in Rome, essentially copying its design7. However, Bramante’s plans were too ambitious, and, by the time of his death in 1514, the supports were too weak to hold up such a dome, so new architects tried their hand at it. After thirty years of no progress on the dome, Michaelangelo was named chief architect in 15468. After changing the exterior design and strengthening the apse support for the dome, Michaelangelo used his Florentine connections to begin construction on the (almost) final version of the dome. Using the same technique as the Florentine Duomo, the dome would change shape from Bramante’s Pantheon design to a near-exact hemisphere. Michaelangelo would die in 1564 before the dome’s completion, but his overall design was largely followed, with only slight modifications to make it slightly taller made by Giacomo Della Porta, with construction on the dome completed in 15909.

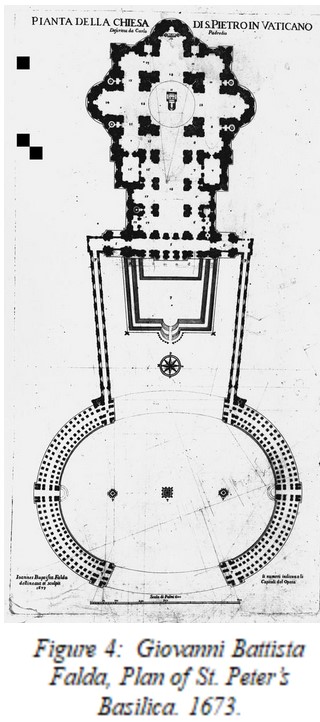

The aforementioned obelisk that was originally on the southern side of St. Peter’s was eventually moved up the hill and repositioned in front of St. Peter’s during the construction. Under Pope Sixtus V in 1586, the obelisk was moved using an elaborate system of ropes and cranes to move this 83-foot-tall stone, placing a cross atop to symbolize Christianity’s triumph over paganism10. By the early 17th century, St. Peter’s Basilica underwent its final changes; the extension of the nave in 1608 and the completion of the piazza and colonnade in 1667. After the colonnade was finished, St. Peter’s now enclosed the entire space of Old St. Peter’s and has remained relatively the same since then besides a few changes commissioned by Mussolini that did not change the image of the existing structures that make up St. Peter’s. By the end of its completion, the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica took over a hundred years. However, building atop Old St. Peter’s, which itself was built upon the Roman cemetery, left St. Peter’s original tomb buried deep underground. The horizontal layering that each consecutive shrine left the body inaccessible since the 9th century. In 1940, an archaeological excavation was done underneath the modern church due to some renovations. Digging near the shrine to St. Peter, they eventually came to a wall, dating to the 2nd century small shrine with the words “Petrus Eni,” or “Peter is here,” inscribed on the side of the wall11. This discovery was the first time anyone had seen the original shrine dedicated to St. Peter in thousands of years, making it a groundbreaking discovery.

While the modern-day architecture and scale of St. Peter’s Basilica is astonishing in its own right, its long and mutative history is ever present in its design and significance. Starting out as an unmarked grave, the space inhabited by St. Peter’s Basilica and Piazza has been witness to dozens of changes and hundreds of visionaries since its veneration by Christianity. The St. Peter’s of today largely follows the same footprint as the original built by Constantine. Some of the greatest artists of Italy have left their fingerprints, from Bramante and Michaelangelo for the architectural exterior and Bernini’s interior design. Crossing the threshold and into the nave, it is easy to become overwhelmed by the sheer scale of interior space. While the loss of Old St. Peter’s is devasting for the historical record, its replacement honors the original intent of venerating St. Peter and Rome’s central role in Catholicism.

Works Cited

Bramante, Donato/Michelangelo Buonarroti, Urbino/Florentine. St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome. 1546-1564. https://jstor.org/stable/community.18146810.

Falda, Giovanni Battista. Plan of St. Peter’s Basilica. 1673. plate: 435 x 218 mm. Rome BH (Dy 100-2730 Gr. Raro). https://jstor.org/stable/community.12396619.

Jerome. De Viris Illustribus ad Dextrum. Translated by Ernest Cushing Richardson. Boston: Wyatt North Publishing, 2012.

Mainstone, Rowland J. “The Dome of St Peter’s: Structural Aspects of Its Design and Construction, and Inquiries into Its Stability.” AA Files, no. 39 (1999): 21–39. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29544154.

McClendon, Charles B. “The History of the Site of St. Peter’s Basilica, Rome.” Perspecta 25 (1989): 33–65. https://doi.org/10.2307/1567138.

Strzempka, Peter. Entrance to St. Peter’s Basilica. 2023. Photograph.

Unknown. (Old) St. Peter’s Basilica Plan. ca. 320-327/333. https://jstor.org/stable/community.12073663.