Tags

By Max Daugherty, History senior.

This is a public presentation produced in HIST4001, Professional Practices in History.

“What will the end of the world look like?” It’s an uneasy question, but most of us have thought it. Today, we may draw on modern popular culture to think about it and imagine zombies overrunning the world. We may draw on scientific predictions or science fiction and imagine natural disasters one after the other. Or we may gain inspiration in prophecies about Judgement Day. All these answers have one thing in common: they are stories that encode the experience, wisdom and feeling of a culture and pass it on from one generation to another, and sometimes one place to another, one culture to another. This article is about one of these stories that survived the test of time. This story begins in ancient Scandinavia or what is now known as Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland.

Ancient Scandinavia already had a pretty good idea of how their world was going to end. In fact, they even had a name for the apocalypse, Ragnarök. Ragnarök for the ancient Scandinavians was not a story, but a prophecy. In their religion known as Norse Paganism, which shared many elements with Germanic Paganism, Ragnarök was the death of the gods and the destruction of the world. The gods such as Thor or Odin would fight gargantuan beasts designed to destroy the world. Those intent on destroying the world would be led by Loki, the god of mischief. The bleak nature and outlook of the story however, didn’t prevent it from living on through their descendants, but rather quite the contrary. Something unique about this tale of demise is its ability to survive in different languages and cultures and to be reincarnated by new story tellers and audiences with new dimensions, ideas and twists.

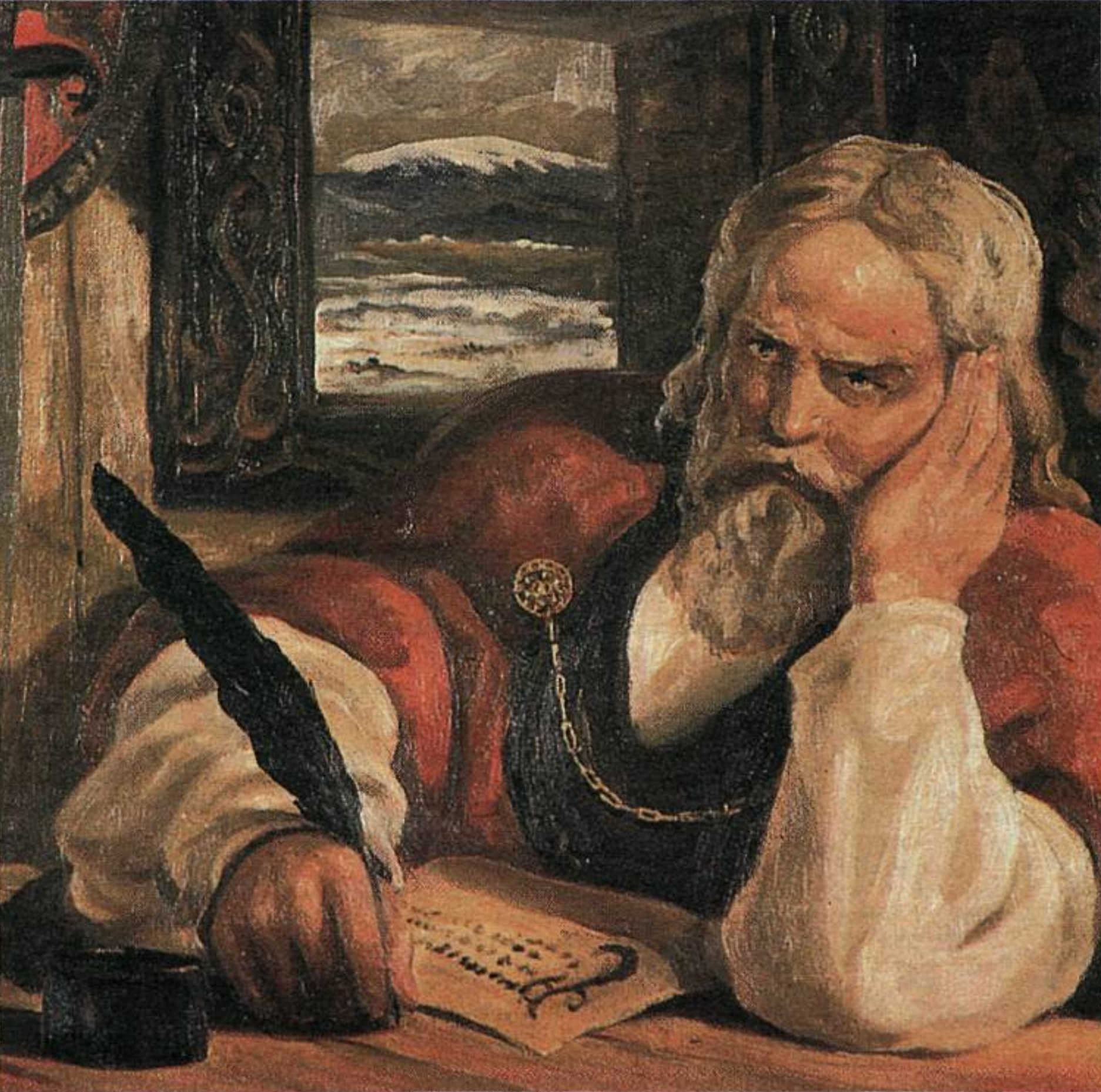

Despite how much we know about Ragnarök now, the truth is we still don’t necessarily know the story as it was told as a prophecy. In fact, many myths and stories shared by the pagans were destroyed by the Catholic church when converting North and Central Europe. However an Icelandic historian, politician and author named Snorri Sturluson, compiled these mythical stories into manuscript in 1220 as a way to save them.

A modern portrait of Snorri Sturlson, Icelandic poet, author and historian, by Haukur Stefansson, 1933

Prose Edda, as his book would come to be known, contained a great volume of Norse myths and legends. From stories of the Gods going on adventures to even the end days or what is now called Ragnarök. Snorri collected and framed these myths as legends and stories, perhaps as a way to avoid persecution from the medieval Catholic church. Thanks to Snorri’s work, the Norse legendarium was able to influence many authors, playwrights, poets and eventually film makers hundreds of years later

One such adaptation is Gottedamerung by the famous German dramatist Richard Wagner. Gottedamerung or as it is translated The Twilight of the Gods, is the final opera in a series of operas created by Wagner based on Norse and Germanic mythology called the Ring cycle. Gottedamerung doesn’t actually focus on the gods and their battle at the end of the world, rather he focuses on a mortal hero named Siegfried, and his relationships with his friends.

Wagner, when he created his operas, wrote them in Germany during an interesting period. Towards the end of his life he saw Germany united in 1871, however most of his productions were produced twenty some years before that. Likely influenced by the growing nationalism in the various German countries and provinces, Wagner chose to do something unique and named the characters after their original names as they would have been in Germany. As such, Thor was Donner and Odin was Wodan. While it might seem like a minor change for a country moving towards unification, the retelling of an ancient prophecy that connected diverse peoples in northern Europe gave late nineteenth-century Germans something to bond over and something to share in common. Wagners operas soon became incredibly popular in Germany and across the world.

However, this would not be the only staged production of Ragnarök. Today many of us know the story from Thor: Ragnarok released by Disney in 2017 as a part of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. For many years Thor had been co-opted as a superhero in Marvel comics and was a very successful hero selling many copies of comics. Disney eventually dedicated him a trilogy of movies with a fourth in production and also featured Thor in their Avengers series.

The comic version of Thor:Ragnarok released in 1966

Thor: Ragnarok is the third in the series of Marvel films, and in my opinion is the best of the trilogy. It strays quite far from the original myth of Ragnarök, drawing characters and storylines from other Marvel movies and comics. Still, the movie retains several of the main characters of the Norse story and towards the end of the film, some inspiration from the original myth becomes evident. Thor and the Hulk fight the giant wolf Fenris and the films main antagonist, Hela the goddess of death. A giant made of fire, known as Surtur is brought back to life and destroys Hela and Asgard, the home of the gods. Thor and Loki, who changes side and becomes a hero, evacuate all of the citizens and board them on a space ship with Thor saying “Asgard is the people, not the place.” The film ends with the citizens and Thor and Loki looking for a new home in space. While the Prose Edda version lacks a spaceship and provides a rather different ending, Snorri concludes with the survival of two humans named Lif and Lifthrasir. This goes to show that the important part of Ragnarök isn’t the destruction of the world, it’s the survival of humanity and its culture. This is the prevalent message in most stories of Ragnarök, it highlights humanities ability to prevail.

Thor: Ragnarok, theatrical release poster

Throughout history and many different audiences and authors, Ragnarök is a story that continues to enthrall us. Every new vision comes with a new message and a new interpretation but the characters and the story share a core. Even a hundred years from now, this historian predicts that people will still learn and be entertained from the tales of ancient Scandinavians.

For further reading:

- Acker, Paul, and Carolyne Larrington (eds.). The Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Mythology. https://b-ok.cc/book/5310009/3347b9.

- Bellows, Henry Adams. The Poetic Edda. New York: Biblo and Tannen, 1969.

- Larrington, Carolyne. The Norse Myths: a Guide to the Gods and Heroes. London: Thames & Hudson, 2019.

- O’Donoghue, Heather. From Asgard to Valhalla: the Remarkable History of the Norse Myths. London, England: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

- Wagner, Richard, Arthur Rackham, Margaret Armour, and Richard Wagner. Siegfried & the Twilight of the Gods. London: William Heinemann : 1911.

- Wagner, Richard. “Vocal Score of Das Rheingold.” Score: BHR5451. Accessed October 10, 2020. http://www.dlib.indiana.edu/variations/scores/bhr5451/large/index.html.