Tags

Written by Professor Ruth Herndon

Written by Professor Ruth Herndon

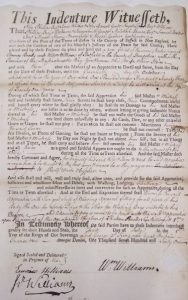

For more than a decade, I have been tracking down information about needy children who caught the attention of Boston’s overseers of the poor in the 1600s and 1700s. For my book project “Children of Misfortune,” I am piecing together the lives of dozens of children who were taken away from their parents and placed in homes considered to be “proper” environments. Some of these boys and girls were illegitimate or orphaned; others had been neglected, abused, or abandoned; still others had parents who had gotten into trouble with the local authorities. For emergency or short-term care, the overseers of the poor (akin to social workers and administrators in our modern-day Departments of Children’s Services) usually placed these children informally with neighbors or relatives. For long-term care, the overseers usually bound the children formally as “poor apprentices.” Thousands of poor apprentice indentures still remain in historical archives. Central to my project is the curated collection of indentures at the Boston Public Library. I have also drawn heavily on the records of the Boston Overseers of the Poor at the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Poor apprenticeship was widely used throughout early America. It was a cost-saving measure, as local magistrates believed “poor” children were likely to become a burden on tax-paying citizens. The overseers bound the children at all ages: some were as young as two or three years old; others were already in their mid and late teens. Masters promised to provide the necessities of life, work training, and some literacy education. Children promised obedience and labor. The contract lasted until adulthood (age 21 for boys and age 18 for girls), so the master could expect a profit: getting the young person’s labor at no cost beyond food, clothing, and lodging. Girls usually worked at “housewifery” tasks of knitting, sewing, spinning, cooking, cleaning, and washing. Boys usually worked as farm hands or in a trade that farmers included in their wider skillset – blacksmith, tailor, carpenter, for example.

My project asks tries to answer the question: “What happened to the children?” Because these children came from poor families, their stories are hidden in the archives. Tracing their stories requires long hours following a name through records of births, marriages, deaths, church membership, census data, military service, property ownership, and more. My research has taken me to many towns in Massachusetts, because the children who came from Boston were often bound into households elsewhere in Massachusetts.

Recently, I have had three opportunities to present my research to various audiences. At each venue, I presented the stories of four boys: Thomas Banks, Benjamin Buffard, Thomas Greenough, and James Taunt. Most apprentices left very few records; in many cases, the indenture is the only document showing they once existed. To find enough information to follow a poor child from a birth record to the indenture to a marriage record and even to a death record – this is a rare window onto the lives of poor people.

Thomas Banks was bound out in 1761 at age 8; he came of age in Hatfield, Massachusetts, in 1773. When he turned 21, he continued on in his master’s home town, working as a shoemaker. He served Hatfield in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, married a Hatfield girl, and lived out a long life in the town that had become his home. He earned a reputation as a practical joker and became so popular with his neighbors that they named his part of town “Banks’ Corner.” He died in 1826 at age 74.

Benjamin Buffard was bound out at age 6 in 1772. He came of age in Rutland, Massachusetts, in 1787. When he turned 21, he traveled from Rutland to Boston to get a copy of his cancelled indenture, proof that he was free. He then moved to Wendell, Massachusetts, where he purchased a plot of land, built a house, married, and began to clear more land. He died suddenly on his land in Wendell in 1800, aged 33, when the tree that he was cutting fell on him. He left behind his wife of only two months. Several years later, Benjamin’s widow Ruth married his friend Joshua Bancroft. They named their first son Benjamin Buffard Bancroft.

Thomas Greenough was bound out in 1774 at age 7. He came of age in Royalston, Massachusetts, in 1788. When he turned 21, he (like Benjamin Buffard) requested a copy of his cancelled indenture from the Boston overseers of the poor. He stayed in Boston, reunited with his brother Samuel (who had been bound to a different master in another town), and tried to earn a living as a laborer. He had been educated by his master, the minister of the Royalston Congregational church, but his apprenticeship did not prepare him for life on his own. His brother died in the Almshouse in 1797. Thomas continued to live on the margin in Boston, using the Almshouse as a refuge during the most difficult years. He died in the Boston Almshouse in 1817 at age 50.

James Taunt was bound out in 1779 at age 5. He came of age in Billerica, Massachusetts, in 1792. He had originally been bound to a master in Bedford, but when that master died, he was re-bound to another master in Billerica. When he turned 21, he married, left Billerica, and moved to Waterford, Vermont. He and his wife had one son and two daughters by 1800. He vanishes from the documentary record after 1800, perhaps having moved on to Canada or to upstate New York. I am still looking for evidence of him and his family.

In March, I presented my chapter on the four boys at the Duquesne University symposium on “Children, Youth & Labor on the Eve of Independence.” The scholars at the symposium gave me excellent ideas for revising the narratives and analysis. In June, I presented these stories again at a talk titled “The Earliest At-Risk” in the Wood County Museum Tea series. For the 70 people who attended this public talk, I connected the experience of poor apprenticeship to the museum’s current exhibit “For Comfort & Convenience,” which features Ohio’s poor farms of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The questions the audience asked helped me revise the chapter again. In July, I presented the chapter a third time at the Biography Workshop at the annual conference of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic, which convened in Boston. I received excellent feedback again and revised the chapter further. As a bonus, I was able to work in various archives for a few days before the conference, continuing my search for information about Boston’s poor apprentices.

These three presentations helped me see Thomas Banks, Thomas Greenough, Benjamin Buffard, and James Taunt through others’ eyes. Comments and questions reminded me what poor apprenticeship looks like in today’s contexts of welfare, child abuse, and family separation. In 2019, state and federal officials would make very different choices than local town leaders made in the 1700s, before foster parenting or adoption were options. But in both eras, vulnerable children present a major problem to a community, and we are still figuring out how to make sure that “no child is left behind.”