Apr

16

Preserve Your Digital Heritage: A Workshop on Archiving Your Digital Photographs

April 16, 2014 | News | Leave a Comment

Thursday, April 17, 12:00 p.m.-1:00 p.m., Pallister Conference Room

This work shop will provide information about creating a long(er)-term preservation strategy for your digital photographs. We will discuss the best practices for the digital preservation of images from an array of mediums including: Digital cameras, cell phones, Facebook, Instagram, and Clouds. Library staff will provide a brief presentation on techniques to preserve your digital heritage and be available to answer any questions you may have about digital preservation. Bring a friend and any digital preservation questions you have. Light refreshments will be provided.

Nov

29

Winners of Local History Publication Award

November 29, 2012 | All, Local History, News | Leave a Comment

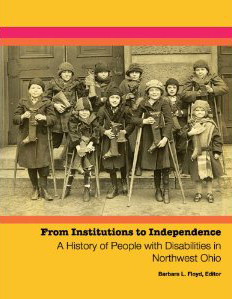

From Institution to Independence is the 2012 Local History Publication Award winner in the Academic Scholar Division

The Center for Archival Collections has revealed the winners of their 2012 Local History Publication Award. From Institutions to Independence: A History of People with Disabilities in Northwest Ohio, edited by Barbara L. Floyd, won in the Academic Scholar Division, and Calamity and Courage: Tiffin’s Battle During Ohio’s Deadly 1913 Flood, written by Lisa Swickard, won in the Independent Scholar Division. Receiving Honorable Mention were Arab Americans in Toledo, by Samir Abu-Absi, in the Academic Scholar Division, and Searching for Lawrence Emmitt, by James Baker, in the Independent Scholar Division. Other nominated works included Thus Fell Tecumseh by Frank Kuron, Henry County During the Great War: German-Americans, Patriots, and Loyalty by Michael McMaster, and The Boy Who Changed the World: Ohio and the Crippled Children’s Movement by Barbara L. Floyd.

The Local History Publication Award was established to encourage and recognize authors for outstanding publications in the field of northwest Ohio history. Eligible works are judged on literary merit, overall significance and contribution to explaining and understanding the history of the northwest Ohio region. Consideration is also given for style, content, accuracy, illustration, and indexes. Two divisions are recognized. The Academic Scholar Division includes works prepared and submitted by authors who are professional writers and academicians, and the Independent Scholar Division includes works prepared by independent or local researchers, amateurs, and other creative writers who do not claim history as a profession. Each Division winner receives a $300.00 cash award and plaque.

Sep

19

Popular Culture Building Part of BGSU History

September 19, 2012 | All, Local History, University Archives | Leave a Comment

Certainly, as students of a modern university, there are things that we expect and accept—for one, that the university’s landscape will be constantly changing. Just as each new generation of students changes, so must the university. The demands of students today are vastly different from those of even ten years ago. The campus structures that served students of the past may not be adequate for students of the future. Those who have been around BGSU for the past few years can attest to how much has changed in just a short time. Unfortunately, the Popular Culture Building fell victim to this kind of progress shortly before the beginning of this school year.

As a current BGSU student, majoring in both history and popular culture, I was among the many current students, alumni, and faculty who were saddened by the decision to demolish the Popular Culture Building at the corner of Wooster and South College. I had traipsed through the building on many occasions, but never really contemplated what it meant, beyond housing the offices of one of my departments. It was a really neat building, though–I could easily recognize that. It was all brick and stone on the outside, with a stylized metal “S” decorating the chimney. Some of the leaded glass windows featured small stained glass pieces, placed seemingly at random. Inside, faculty offices occupied areas that had once made up a small family home. Walking into what had been the basement rumpus room during the tenure of President McDonald was like walking into the past.

Since the 1970s, the house had served as a home to the internationally recognized department of Popular Culture, so the decision was not without controversy. Though this decision was part of the master plan, Popular Culture faculty maintained that they did not know of the impending demolition until they were asked to move their offices in late July. At the time of the move, the house did not appear on the map of proposed changes to campus. The news of the decision first reached the rest of the BGSU community through an article in the Bowling Green Sentinel-Tribune on July 21, 2012, which detailed the university’s decision.

I honestly did not know what the little brick house meant to me until the day that I found out that it would be razed. As a student of history, I hate to see the destruction of things of potential historical import. Thinking about the destruction of the Library of Alexandria upsets me, and that occurred during the reign of Julius Caesar. (Depending on which historian you ask, at least.) The demolition of the Popular Culture Building hit a bit closer to home. As a student of Popular Culture, the house was the physical embodiment of a discipline that opened an entirely new world to me. BGSU is literally the birthplace of popular culture as a field of study, and it was born within those brick walls. For me, and for so many others, the house was much more than just bricks and mortar.

In 2009, several buildings on campus were evaluated by an engineering team and recommendations were made about the future of those buildings. Some buildings, such as University Hall—one of the oldest at BGSU—were recommended for renovation. The house at 838 East Wooster Street, however, was recommended for demolition. The fifteen year master plan also included plans to renovate, replace, or demolish other buildings throughout campus. The demolition of the Popular Culture building will join the lot to its neighbors, creating a potential site for a new health center, to be built and operated in conjunction with Wood County Hospital by the start of the 2013 – 2014 school year.

Even as explanations began to roll in from the administration in the following days, a groundswell of protest grew. Faculty, alumni, and current students rushed to try to save the house. An online petition at signon.org quickly gathered over two thousand signatures from all over the world. The local media covered news of events, including a protest rally on the lawn of the house on July 31, 2012. I was one of roughly fifty people to attend the rally, holding a neon pink sign which read “Honk if You Love Pop Culture.” Other signs held by participants included, “We are BGSU,” “Pop Culture Lives Here,” and “Save This House,” a refrain which was periodically chanted.

Even as explanations began to roll in from the administration in the following days, a groundswell of protest grew. Faculty, alumni, and current students rushed to try to save the house. An online petition at signon.org quickly gathered over two thousand signatures from all over the world. The local media covered news of events, including a protest rally on the lawn of the house on July 31, 2012. I was one of roughly fifty people to attend the rally, holding a neon pink sign which read “Honk if You Love Pop Culture.” Other signs held by participants included, “We are BGSU,” “Pop Culture Lives Here,” and “Save This House,” a refrain which was periodically chanted.

Though our protest garnered attention within the community and from outside it—it was the lead story on Toledo’s ABC affiliate that night—the university concluded that the demolition of the building was integral to the master plan and followed through with their decision. The building was cleared by early August and several artifacts including leaded glass windows, solid wood banisters, crystal doorknobs, and original cabinetry were removed in preparation. Demolition was completed ahead of schedule on the morning of August 10, 2012.

How could one small building create such an outpouring of protest? Much of the motivation behind the campaign to save the building was not tied to its emotional significance, but to its historical significance. The Popular Culture Building was a landmark of the university and the Bowling Green community for several decades. It served as home to three university presidents and housed one of the most unique departments that the university has to offer. Even before it was purchased by the university, the house had an interesting history.

Originally built in 1932 by Bowling Green resident Virgil Taylor, the home had been ordered through the local Montgomery Ward department store. Catalog homes were a popular housing option in the early 20th century. Consumers could select from a catalog of designs and have all the necessary building materials delivered directly to them. Kit homes began to lose popularity with the onset of the Great Depress in the 1930s and fewer survive with each passing year. Though there are other examples of kit homes in Bowling Green, none can boast the unique origins of the one built by Mr. Taylor.

The building baffled researchers for many years. The Board of Trustees minutes discussing its purchase refer to it as a “Montgomery Ward home,” as do several articles and other official university documents. Yet the design of the house did not seem to fit any that appeared in the Montgomery Ward catalogs. In an article probably published in the BG Monitor during the 1970s or 1980s, this confusion was discussed by Pat Browne, the wife of Popular Culture department founder Ray Browne. A pioneer in the discipline in her own right, Mrs. Browne said that it was believed that the house was ordered from Sears, since Sears offered such a neo-Tudor style home called the “Lewiston.”

In 1985, a student gathered information to submit the house to the National Register of Historic Places, but did little to quell the confusion. One source of information was a letter written by the last tenant of the home before it was purchased by the university in 1937. The woman indicated that she and her husband, a manager for the local Montgomery Ward department store, had made a deal to rent the home from the company. In January of 1936, Montgomery Ward had taken possession of the home, Mr. Taylor apparently having defaulted on a mortgage that was financed through them. Though Montgomery Ward did not intend to lease the property, the insurance required that it be occupied and little progress had been made toward selling it. This letter reinforced the conclusion that the house was purchased through Montgomery Ward.

Not until very recently did the true story behind 838 East Wooster Street come to light. Thanks to the research and assistance of kit home experts Rosemary Thornton and Rachel Shoemaker, we were able to solve the mystery of the house’s origins. The kit was certainly purchased through Montgomery Ward. Evidence of that could be found in the fixtures within. It was also most certainly identical to the Sears “Lewiston” model; Montgomery Ward had never featured anything similar. The debate over whether the home was a Montgomery Ward or a Sears kit was finally solved. Amazingly, it was both.

The university purchased the building in 1937 to serve as the home of the new president, Dr. Roy Offenhauer. Eventually, Presidents Frank Prout (1939-1951) and Ralph McDonald (1951-1961) made their homes there. President Ralph Harshman (1961-1963) did not live there during his short tenure. He and his wife already had a private residence in the city and chose not to relocate.

During President McDonald’s tenure, the house was the site of one of several large protests that took place in March 1961. Though no pictures of the event exist, newspaper articles describe the protesting students who blocked traffic in front of the property, set a bonfire alight in the middle of the street and burned an effigy of the president, directly in view of the house. Contemporary news articles blamed non-students who had joined the fray, but the message was clear. President McDonald stepped down within a few months of the protest, which had largely been spurred by his strict social policies.

When President William Jerome (1963-1970) arrived, it was clear that the house no longer suited the needs of a university president. In response, the University purchased the third presidential residence on Hillcrest Drive, and the house on Wooster became, in turn, the home of the Alumni Center, the Graduate College, and eventually the Popular Culture Department in the late 1970s.

Under the careful tutelage of Dr. Ray Browne, the discipline of Popular Culture was born and nurtured at the university. The brick house at the corner of Wooster and College Street was a perfect home for the new department, which will celebrate its fortieth anniversary in 2013. The house itself was truly a piece of popular culture. Certainly faculty, alumni, and current students held emotional attachments to the building. After all, BGSU was the first university in North America to offer a degree in Popular Culture, and even today it remains the only university to boast a department devoted to the discipline.

That small brick house will certainly be missed. Those of us who saw it as more than just a building at the corner of a busy intersection will always be saddened by its loss, even though we expect and accept that the university will be perpetually changing. Though the house is gone, it continues to live on in the history of the university. The Popular Culture Building joins others like the Natatorium, Alice Prout Hall, the Falcon’s Nest, and Saddlemire Student Services Building. While these buildings no longer have a physical presence on campus, they continue to be remembered. When the plans to build the new health center come to fruition, the intersection of Wooster and South College will continue to be a reminder of the unique building that once occupied the corner lot.

–Rebecca Denes

Sources:

pUA 1936 838 East Wooster Street, Bowling Green, Ohio. Background materials, 1901-2012. Includes all known history of the building and all available information about the campaign to save it.)

“Homes of the Presidents” (Centennial Memories) http://memories.bgsu.edu/exhibits/show/prezhomes

“Sears Modern Homes” (Rosemary Thornton) http://www.searshomes.org/