Nicholas Clark Bowers

As we endure the COVID-19 pandemic, it is a worrying and stressful time. And to complicate matters even further, we are living in a truly global age when we can receive information in real time. The dissemination of misinformation, also known as “fake news,” has become almost synonymous with social media. I must admit that I have fallen for false stories online more times than I care to remember. During the pandemic I have seen an up-tick in the amount of questionable information that make me ask “Wait, really?” only to look into it further and see a complete fabrication, and it would seem I am far from the only one. I wondered how our previous generations experienced fake news, and what lessons we may be able to take from them. What I found is that the concept of fake news hampering disease response and breaking down social cohesion is nothing new.

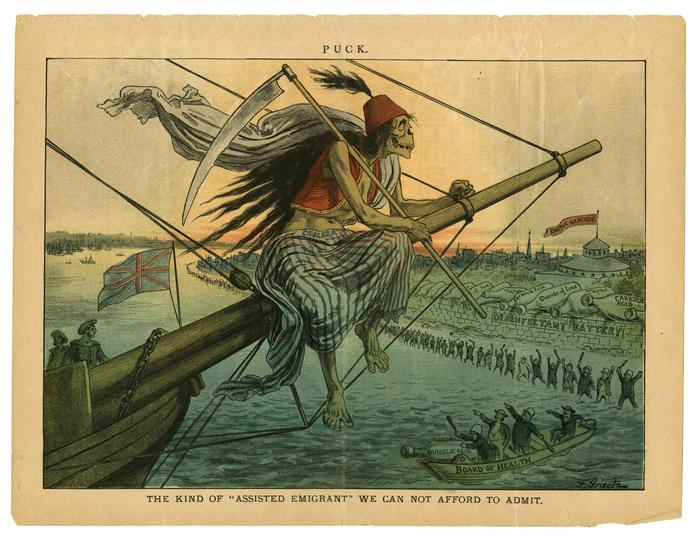

Historically, there have been two major ways in which misinformation has spread amongst the populace. The first is through rumors and speculation that move between citizens who are hoping for some clarity and comfort while their world changes around them. This desire for comforting information leads to stratification of society as people search for someone to fault for the suffering and misery they are seeing. These feelings are part of a concept known as disease narratives, explanations that circulate through society during pandemic as people apply them to their own world. Common narrative includes xenophobia, and government related conspiracies. We can even see this narrative playing out in regarding COVID-19, with Asian-Americans being used as a scapegoat by the rest of the general population of the US amidst the pandemic. This phenomenon is like the rumors that circulated during the AIDs epidemic of the 1980s. Because of a misunderstanding of how the disease spread, AIDs were associated with the LGBT community. People who were openly part of this community faced public discrimination because the general population incorrectly believed this community was a risk factor and should be shunned as such. Narratives such as these divide societies in times of crisis, basing actions and feelings on fear, rumor, and misinformation rather than facts.

Historians do the work to understand the origins of these feelings. Understanding the narratives that arise from the emergence of a new disease allows public officials and healthcare workers to better prepare themselves for the pandemic. Looking into past pandemics and understanding misinformation of the past gives valuable insight on the human psyche, and how it deals with a national or global pandemic. One example of this is the “panic” and misinterpretation of government efforts comes from the plague pandemic of the 1890s in colonial India. Local misinterpretation and distrust of the colonial authority’s disease control efforts led to widespread panic that divided the land and facilitated disease spread. A modern day parallel of this would be protests demanding that states reopen, and government officials step back have begun because of the COVID pandemic. In mid-March, protestors began gathering in front of the Ohio Statehouse, demanding the governor and department of health allow them to return to work.

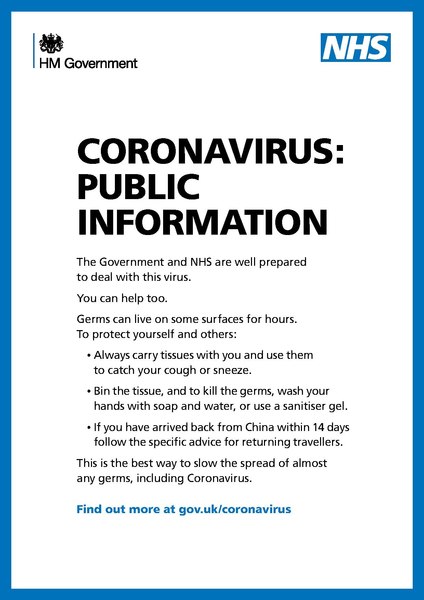

Misinformation from organic sources is not the only way this phenomenon happens, sometimes it needs some “help.” Spreading disinformation is often of interest to foreign adversaries who hope to sow division within their opponents. This phenomenon played out in Africa during the height of the AIDs epidemic, turning the disease into a Cold War ideological battleground. Geopolitical misinformation is thought to be happening as we speak. European Union officials believe that Russian and Chinese propaganda campaigns to undermine COVID response efforts. Misinformation in both cases fits in well with disease narratives and how a panicked public will predictably react to an unseen enemy ravaging their community. These narratives often lead to collapse of social cohesion, fostering suspicion between neighbors and government authorities who are aiming to mitigate the disease. Thus, it is in the best interest of the government to take steps to earn public trust when attempting to mitigate an outbreak. It is imperative that governments and private organizations take measures to maintain social cohesion by promoting a fact-based approach to evaluating sources. The government of the United Kingdom has done that in the current pandemic by launching the SHARE campaign to prove the public with a set of guidelines so they can evaluate the legitimacy of sources themselves.

Misinformation is a threat to be taken seriously, and with our entrance into a global era of information, the stakes could not be higher. As we slog through the COVID-19 pandemic, we are acutely aware of the effect it is having on our society as well as our health. Governmental agencies as well as private companies are working to stem the tide of misinformation about the virus, it is important to know the origins of these rumors and what in our culture leads us to be susceptible to deception by these dubious sources. By looking back to past pandemics, we are truly looking forward to how we can shape a more secure tomorrow for our current pandemic and beyond.