[Note: this description is adapted from the previously published article, “Seeing Double: Collecting Sweet Valley High.” Journal of American Culture, vol. 42, no. 1, 2020, pp. 27-40.]

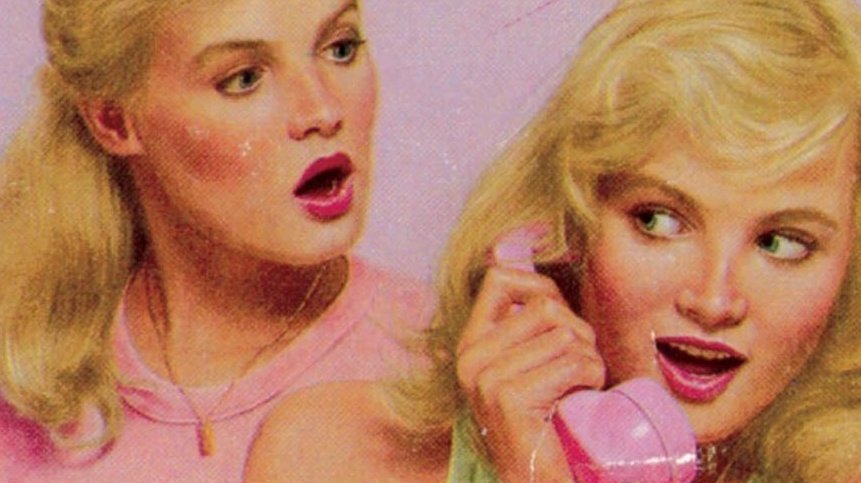

The Sweet Valley High series was launched by Random House in 1983. Strongly influenced by the commercial success of the popular paperback romance novel, publishers saw an opportunity to capture the adolescent market. “Conceived by author Francine Pascal, the series eventually was written by numerous authors all using the pseudonym Kate William; new installments were released monthly. The series follows the adventures of the enigmatic identical twins, Jessica and Elizabeth Wakefield, and their friends in the fictional upscale southern California beach town of Sweet Valley. In the introduction to my book, The twins, as every book emphasizes within its first few pages, are beautiful with silky blond hair, aquamarine eyes, and perfect size six figures. However, that is “where the similarities end.” Personality‐wise, Elizabeth and Jessica are polar opposites. Elizabeth is studious, dresses conservatively, and prefers a monogamous, serious relationship. Jessica is impulsive, flirtatious, and loves to socialize. This dichotomy is ripe for basic Freudian analysis (Swanston 187), placing hedonistic Jessica as the id and responsible Elizabeth as the superego.

The enormously popular book series lasted for a decade. The adventures of the high school characters, however, seemed to reflect teenage tropes of the 1950s instead of the time they were written. Characters warned about the dangers of drugs and falling into the wrong crowd. Sweet Valley is seemingly populated by teen archetypes: the rich snob, the handsome quarterback, the annoying nerd, and the popular cheerleader. Those who were not popular were in stark contrast to the world of the twins: overweight, unattractive, awkward, and economically disadvantaged students who were always troubled and flawed, unless, of course, they became more like the twins.

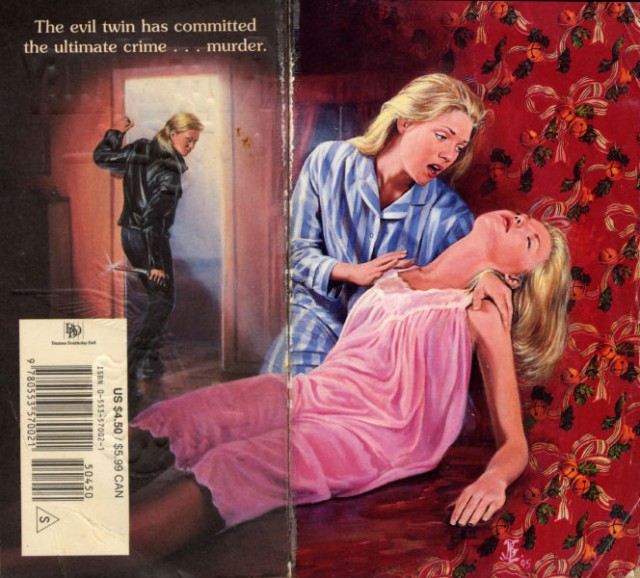

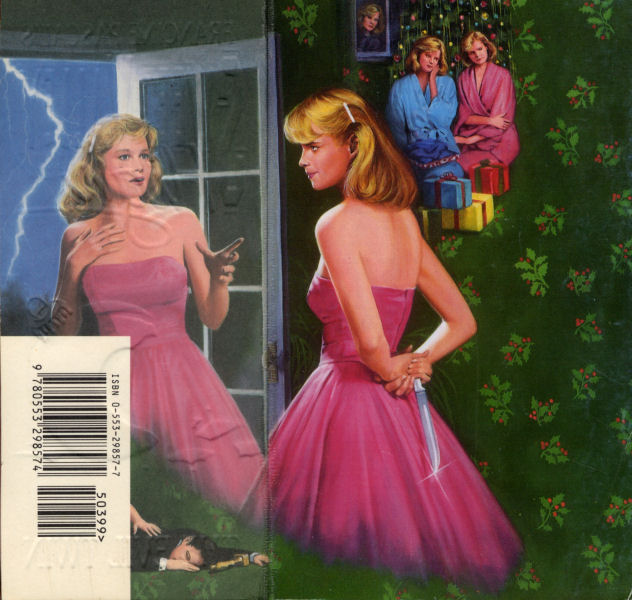

Even though Sweet Valley High had a successful formula, eventually changes had to be made to keep it relevant and on bookshelves. After 100 books, the series introduced the first “magna edition,” The Evil Twin (1993), and its later sequel, Return of the Evil Twin (1995). From a publishing standpoint, these served to rejuvenate the series and to “up the stakes” of the characters. To collectors, this represents the “turning point,” when, during their first read, they suddenly felt that the curtain had been pulled back.

As discussed earlier, the campiness of a text is ultimately decided by the reader, especially when comparing past texts with the current culture It is difficult to say if this is an esthetic choice or a purposeful acknowledgment of the series’ own unrealistic plots. In The Evil Twin, Margo is a troubled teenager who suffers abuse while being shuffled through a series of foster homes. When Margo reaches Sweet Valley, she stalks the twins to gain information about them and to seamlessly take over their identity. In her observations, she notes the cloying, patronizing personality of Elizabeth Wakefield and the selfish, spoiled personality of Jessica Wakefield. Margo finally thinks and says what the readers have been pondering for decades. Margo, and later, Nora, enact revenge on the twins because she believes that the twins have taken what was kept from her for her whole life. The Evil Twins plan to literally murder the twins and take over their popular, perfect lives, can be considered an exaggerated fantasy for many teen girls who felt they did not live up to standards.

Supplementary Reading

Swanstrom, Lisa. “Nora Unchained and “Margo Rising”: Evil Twins at the Limits of Genre in Francine Pascal’s Young Adult Franchise.” Extrapolation, vol. 58, 2017, pp. 181–208.

Swanstrom analyzes the books from a genre analysis, citing the emergence of the Evil Twin(s) The switch from melodrama to horror betrays the cherished social conventions that the teen melodrama holds as sacrosanct, and the differences between the two bring these social conventions into relief, exposing the faulty assumptions upon which they rest” (194). Whereas the relatability of the first 99 books was dubious, The Evil Twin descended into heights of the fantastic. Swanstrom observes that the sudden switch in the genre is transformative: “The switch from melodrama to horror betrays the cherished social conventions that the teen melodrama holds as sacrosanct, and the differences between the two bring these social conventions into relief, exposing the faulty assumptions upon which they rest” (193). If the actions of the characters were socially unrealistic, the events in The Evil Twin, and its later inevitable sequel, Return of the Evil Twin, are outlandish. Swanstrom states that with the acceptance of the twins’ doppelgänger who, as we find out in the sequel, has her own twin separated from her at birth, the “books enter the domain of the truly uncanny, with all its malicious, supernatural, and horrific import” (129). Using one of the most infamous soap opera twists, an evil lookalike, is delightfully self‐aware.

Although a revenge plot, especially with a villainess, is common to melodrama/romance, it can pull the ideas into the realm of horror. When looked at in horror, the reasons why Nora and Margo want revenge is brought into clarity. Nora and Margo are a stand-in for the reader, who gets o act out their fantasies of killing off the characters and their perfection. Nora and Margo feel they have been robbed of the perfect charmed life that Elizabeth leads, resentful that they were given the charmed life that teenage girls dream of. This could be a stand-in for the frustrations of the readers who never achieve the impossible goal. Sweet Valley High is aspirational but The Evil Twin plots are catharsis.

Ross, Andrew. “Uses of Camp,” in No Respect: Intellectuals & Popular Culture. Routledge, 1989.

Camp and its parameters do not have a consensus within academia. Sometimes connected to queerness, specifically male sensibility, it is a performance of “semiotic excess.” A text can become camp after a matter of time when tastes and cultural markers change. Ross writes, “The camp effect… is created not simply by a change in the mode of cultural production, but rather when the products. of a much earlier mode of production, which has lost its power to dominate cultural meanings, become available, in the present, for redefinition of codes of taste” (139). In this way, a camp reading of a text can be an enjoyable appreciation of an older text that seems outdated. Andrew also considers camp as a type of excess labor derived from the text:]“In liberating the objects and discourses of the past from disdain and neglect, camp generates its own kind of economy. Camp, in this respect, is the re‐creation of surplus value from forgotten forms of labor” (151) The excess labor I the meta-enjoyment of the cultural artifact, to appreciate its out of place, older values. Sweet Valley High is a book series that many original readers can simultaneously feel nostalgia for but also acknowledge how it deserves critical inquiry. Camp is used through a feminist lens of older texts, which are easy to dismiss as too problematic and outdated but to appreciate the distance between the cultural milieu between the past and present. The current day reading of Sweet Valley High, and especially the appearance of Margo and Nora, have been redefined through a camp lens by those former readers who are now adults, as evidenced by anti-fan blogs, podcasts, and Buzzfeed quizzes.

Villainesses in popular culture often acquire a camp following and are often read as overly flamboyant, ridiculous, and melodramatic. They are appreciated for their large emotional gestures and at the same time their outsider status. To some, camping a Villainess may seem to further trivialize the character, but it can also celebrate her status as an outsider and a troublemaker.