Platyhelminthes: As If Worms Could Get Any More Gross

Posted in Phyla on September 22nd, 2017 by kyldougDeducing the Organism

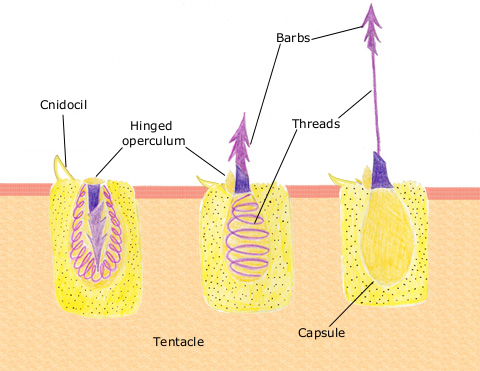

This week, we were presented with an extremely alien picture. The organism had multiple orifices along the same plane, as well as a deep groove along its ventral plane. I could tell it was a worm, as it looked like it had a more solid body structure than the siphonophore, which I previously thought was a worm. I perused the textbook, taking advantage of the fact that it moves in terms of least complex to most complex, and eventually I found the trematodes of phylum Platyhelminthes.

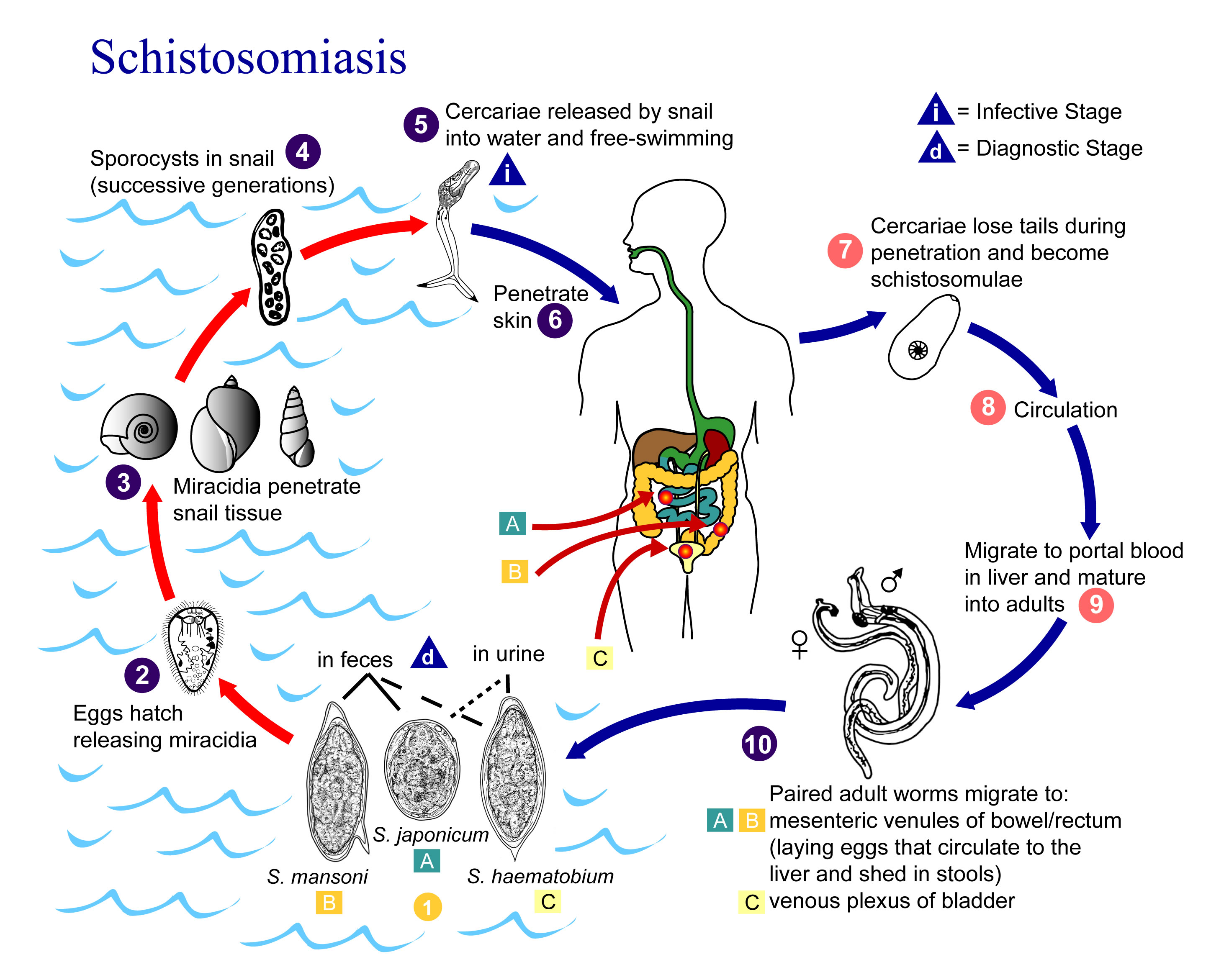

The various stages of the trematode life cycle Source: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Trematode_lifecycle_stages.png

Platyhelminthes As A Whole

Platyhelminthes is one of two major phylum containing a diverse set of worms, with the other being Annelida. Platyhelminthes are characterized by flat bodies with no segmentation, with three developed skin layers. Some of these organisms are free-living organisms, while others are parasitic and rely on hosts to fulfill their needs (Berkeley, n.d.). Phylum Platyhelminthes is a very diverse phylum encompassing many types of organisms. Everything from tapeworms in cow intestines to marine flatworms are included in Platyhelminthes, and with diverse organisms comes diverse reproduction.

Sexual Reproduction: No Saxophone Necessary

Phylum Platyhelminthes is capable of reproducing both sexually and asexually, but as with most organisms, sexual reproduction is more beneficial to the organisms as a whole. The most basic sexual reproduction occurs in the turbellarians, which engage in the romantic process called “penis fencing”. All turbellarians are hermaphrodites, so when they engage in this act they attempt to impregnate one another by dueling with their penises. Once pregnant, the eggs are concealed in a protective cocoon and released. When they hatch, the eggs will be miniature adults, and continue their life cycle (Science Alive, n.d.).

Next in terms of complexity are the monogeneans. Monogeneans are parasitic, and reproduce away from their hosts (Wikipedia, n.d.). The two organisms mate similar to the turbellarians, however the eggs hatch into a highly ciliated larvae called oncomiracidium that infect hosts and continue to develop (Monogeneans, n.d.).

The next most complex group is the cestodes, or tapeworms. The hermaphroditic cestodes exchange spermatozoa with one another via their genital pore. From there, the gravid segments (proglottids) are passed through the host’s feces and the eggs are hopefully consumed by another organism. This new organism becomes an intermediate host and allows the cestode to advance to its juvenile stage. If all goes well (for the worm), a new primate host will consume the infected organism containing the juvenile worms, which will then mature in the new host and repeat this process (Wikipedia, n.d.). For a video on cestodes and their reproduction, click this link.

A diagram of the lifecycle of a cestode Source: https://es.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archivo:Taenia_LifeCycle.gif

Finally, the trematode peaks the Platyhelminthes sex complexity. The female slides into the male’s genital groove where fertilization occurs, and the eggs are excreted into a freshwater source. From there, the eggs hatch and release miracidia, which find an intermediate host, usually in the form of a mollusk. From here, the sexual reproduction ends and it becomes asexual to complete the rest of the trematode life cycle.

A mating pair of Schisosoma mansoni Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schistosoma_mansoni#/media/File:Couple_of_Schistosoma_mansoni.jpg

Asexual Reproduction: Attack of the Clones

For most Platyhelminths, the asexual reproduction is similar to the sexual, however the offspring will be perfect clones of the parent. Since most Platyhelminths are hermaphrodites, they are capable of self-fertilization, albeit rarely. Most Platyhelminths try to hybridize with another worm to keep their population diverse. The major exception to this is the trematodes, which utilize both sexual and asexual reproduction in their lifecycle. When in their intermediate host, the worm larvae will reproduce asexually before moving onto a final host where they complete their life cycle.

Schistosoma heamotobium: Burrowing Their Way Into Your Heart

What differentiates the organism of the week, S. haemotobium, from the rest of the trematodes is their complex phases during their life cycles. After the miracidia are in the mollusk’s body, they develop as sporocysts which multiply and release as cercariae into a water supply (Stanford, n.d.). From there, chemical signals allow the cercariae to find a host and burrow into their livers where they mature into adults. A diagram of schistosoma reproduction can be found below (IARC, 1970).

A detailed life cycle diagram of Schistosomes Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Schistosomiasis_Life_Cycle.png

References

Cestoda. (2017, August 25). Retrieved September 22, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cestoda

E. (n.d.). Monogeneans: Monogenea – Behavior And Reproduction. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from http://animals.jrank.org/pages/1521/Monogeneans-Monogenea-BEHAVIOR-REPRODUCTION.html

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans. (1970, January 01). SCHISTOSOMA HAEMATOBIUM. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK304343/

Lie, L. I. (1970, January 01). Platyhelminthes. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from http://sciencealive-flatworms.blogspot.com/2011/09/class-turbellaria_28.html

Monogenea. (2017, September 04). Retrieved September 22, 2017, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monogenea

(n.d.). Retrieved September 22, 2017, from http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/platyhelminthes/platyhelminthes.html

Schistosoma haematobium (blood flukes). (n.d.). Retrieved September 22, 2017, from https://web.stanford.edu/class/humbio103/ParaSites2004/Schisto/website.html

Trematode Infection. (2017, September 19). Retrieved September 22, 2017, from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/230112-overview